A Thai Novel: From the Inside? On Veeraporn Nitiprapha, The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth, 2013, translation 2018

Main Article Content

Abstract

Modern Thai literature has been given insufficient attention overseas because of a dearth of good, easily available translations and critical texts. This situation has begun to change, with the excellent translation of Veeraporn Nitiprapha’s SEA Write Award-winning novel and some other texts. An insight into this burgeoning literature can now be gained outside Thailand and beyond the Thai language. This article intends to introduce the novel, to look at some of its distinctive techniques, to indicate how this novel lives in a Thai cultural world, and to see how it can be used to understand some particular kinds of modern self.

Article Details

References

As warily lamented by the former Australian ambassador to Thailand, James Wise, in his recent, clear-headed book for neophytes of Thai history, politics, and law: Thailand: History, Politics and the Rule of Law, Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2019, viii.

I have been helped in my endeavours by a very patient and broadly cultured Thai person, Phaptawan Suwannakudt, and her assistance in thinking about the Thai nuances of Veeraporn’s text has been invaluable. The article has further been greatly assisted through the perspectives of Thai and non-Thai scholars of Thai literature and society, some of my debts to whom I acknowledge in endnotes, and in a separate bibliography. I also wish to thank the editor of The Journal of the Siam Society and one anonymous reader for their very useful critical comments.

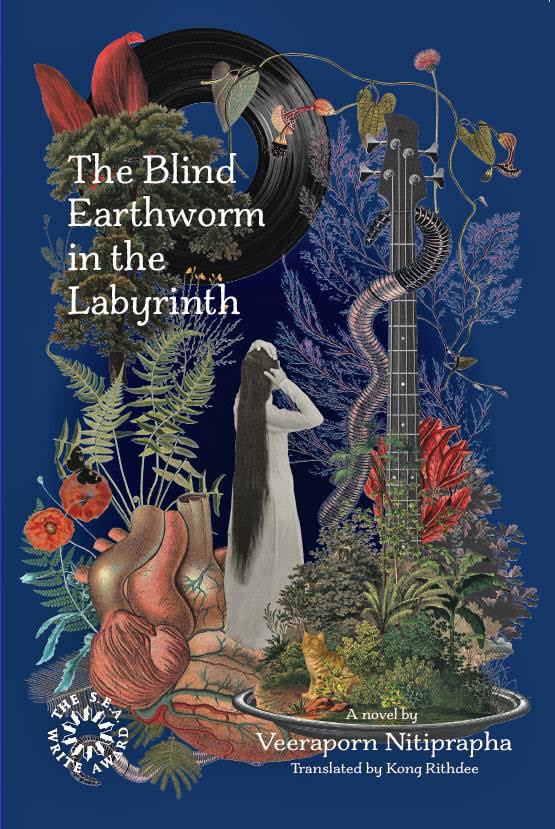

Veeraporn Nitiprapha, Saiduan tapoot nay khaa wongkot, Bangkok: Dichan, 2556/2013; translated by Kong Rithdee as The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth, Bangkok: River Books, 2018. Winner of S.E.A. Write award for fiction in 2015.

Veeraporn Nitiprapha, Phutthasakkarat atsatong kap songjam khong songjam khong meo tam (The Twilight of the Century and the Memory of the Memory of a Black-rose Cat), Bangkok: Dichan, 2559/2016); S.E.A. Write Award for fiction 2018.

Miguel Ángel Asturias, Men of Maize (Spanish original 1949, translated by Gerald Martin), London: Verso 1988.

There is, by the way, no ‘evil man of God’ character such as played in film by Robert Mitchum in The Night of the Hu.

Veeraporn Nitiprapha, The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth, translated by Kong Rithdee, Bangkok: River Books, 2018; hereafter, Kong translation. Hereafter paginations given as Kong translation, 123.

Kong translation, 40.

See Amos Oz, A Tale of Love and Darkness (Hebrew original 2003, translated by Nicholas de Lange, 2004) London: Vintage Books, 2017. One such list is at the bottom of page 147.

Veeraporn Nitiprapha, Saiduan tapoot nay khaa wongkot, Khrungtheep, Samnak Phim Dichan: P.S. 2556 (2013) [read in 10th printing of P.S. 2559 (2016); hereafter, Original, 11.

Original, 22.

Original, 45. Kong translation, 41.

Original, 30.

Original, 30.

Kong translation, 26.

Original, 45.

Kong translation, 41.

Original, 215.

Kong translation, 172. Veeraporn elsewhere uses an explicit scene of shimmering:

He saw nothing except the shimmering, shapeless haze of sunlight filtered through the surface and illuminating a dead tree. Kong translation 50.

Kong translation, 42.

Kong translation, 69.

For a discussion in part of Thai food aesthetics and the problems of negative appraisal in a comparison of Thai and Japanese food aesthetics, see John Clark, ‘Food Stories’, Gastronomica, Spring 2004, 4, 2.

Eric Auerbach, Mimesis: the Representation of Reality in Western Literature [original written in Istanbul 1942-45, published Berne, 1946, translated by Willard R. Trask from New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1953, 70-75, 99-121.

Kong translation, 104-11; original, 134-142.

Kong translation, 140-146; original, 176-184.

See Jack Goody, and Ian Watt, ‘The Consequences of Literacy’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 5, no. 3, April 1963, 234.

See the last chapter of João Guimarães Rosa, The Devil to pay in the Backlands (translated by James L. Taylor and Harriet de Onís, Brazilian Portuguese original Grande Sertão: Veredas, 1956) New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963, 485; fFirst French translation, Paris; Albin Michel, 1965, second French translation, Paris: Albin Michel, 1991.

See inter alia, Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen), ‘The roads around Pisa’, in Seven Gothic Tales, London: Putnam, 1934, 1948.

Miguel Ángel Asturias, Men of Maize (Spanish original 1949, translated by Gerald Martin), London: Verso 1988; Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude (Spanish original 1967, translated by Gregory Rabassa), London: Cape, 1970.

On the origins of the term ‘marvellous real’ in Weimar Germany, see Irene Guenther, ‘Magic realism, New Objectivity, and the arts during the Weimar Republic’, in Lois Parkinson Zamora and Wendy B. Faris, Magical Realism: Theory, History, Community, Durham N.C., Duke University Press, 1995, 61.

Chris Baker, and Pasuk Phongpaichit, ‘Gender, Sexuality and Family in old Siam: Women and Men in Khun Chang Khun Phaen’, in Rachel V. Harrison, ed., Disturbing Conventions: Decentering Thai Literary Cultures, London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014. See The Tale of Khun Chang, Khun Phaen: Siam’s folk epic of love, war, and tragedy, translated by Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit, Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2010.

Kong translation, 148.

Kong translation, 45.

Kong translation, 163.

Kong translation, 166.

Kong translation, 150.

Kong translation 154-155. See S. J. Tambiah, Buddhism and the Spirit Cults in North-East Thailand, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970, 312-326, for a discussion of the ‘afflictions caused by malevolent spirits’, including phob on 318. Of course, the beliefs in spirits and participation in cults in Thailand are very complicated between regions. See Paul Cohen and Gehan Wijeyewardene, eds, ‘Spirit Cults and the Position of Women in Northern Thailand’, Mankind (published by The Anthropological Society of New South Wales] 14, 4 (August 1984).

Veeraporn Nitiprapha, Saiduan tapoot nay khaa wongkot, 4. Phaptawan Suwannakudt and I translate the last paragraph as:

I wrote the first sentence in the capital city deeply darkened with smoke and covered with blood. It was done with the sound from a sigh of relief, which covered and buried the common-sense that had passed away. I had hoped that the story would not end up in despair. However, when it arrived at the last phrase there was only a bitter-sweet love story of ‘her’ and ‘him’, without room for ‘us’ at all. This was a story about the land, which used to be tender and gentle, long, long ago.

For example (Kong translation, 172: Cut to: the black rectangle of his window in the room cobwebbed by loneliness…

Veeraporn casually (or sarcastically) mentions the great 1976 turning point of Thai political murder, almost as if the reference was in passing, and only part of a barely significant background historical landscape.

The massacre of 6th October [1976] was twelve years past and its memory had begun to fade. People were no longer even sure it had actually happened. (Kong translation, 60)

Kong translation, 201.

In her scintillatingly funny interview at CMU Bookfair found at www.youtube.com/watch?v=uD7hrI1YEzQ