Dominant Masculinities and the Lure of the Rural Idyll in The King of Bangkok

Main Article Content

Abstract

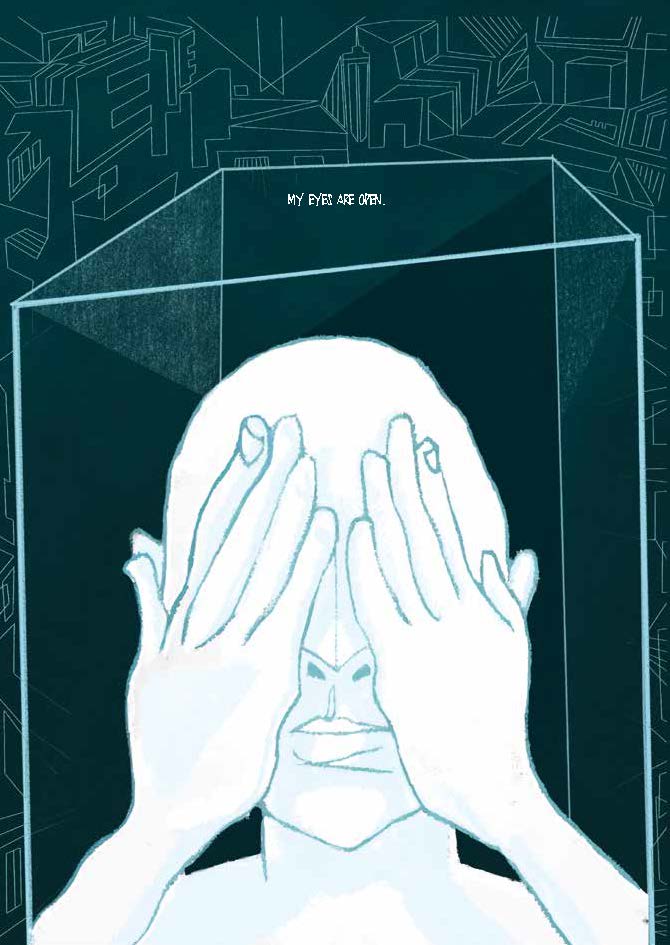

This article provides a critical engagement with The King of Bangkok, a 2021 graphic novel by Claudio Sopranzetti, Sara Fabbri and Chiara Natalucci. The novel deploys an original mode of presenting detailed ethnographic research, and makes extensive use of contemporary imagery such as Thai movies including Pen-ek Ratanaruang’s Monrak Transistor (2001). The authors grapple with the complexities of telling a story covering a fifty-year period of Thai politics to a foreign readership outside the academic realm. As a graphic novel, the work falls under the hyper-masculine influence of the “comic book” form, with its traditional emphasis on the male super-hero, including a troubling tendency to personify Bangkok as threateningly female, and to play down the significance of women, especially in the Red-Shirt movement. This stands in contrast to contemporary Arab feminist writers of graphic novels on protest and uprising. Given that the Thai translation of the work as Ta sawang (Open Eyed, or Awakened) was very popular, what does the novel’s final resolution imply for the political “awakening” of the mass? And how does this text compare with key Thai fictional radicals and anti-heroes from the novels and short stories of 20th-century Leftist writers such as Siburapha, Seni Saowaphong and Wat Wanlyangkun?

Article Details

References

Aldama, Frederick Luis (2021), ‘Gender and Sexuality in Comics: The Told, Untold Stories’, in Frederick L. Aldama (ed), The Routledge Companion to Gender and Sexuality in Comic Book Studies, Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 1-12.

Anderson, Benedict R O’G and Ruchira Mendiones (1985), Literature and Politics in Siam in the American Era. Bangkok: Editions Duang Kamol.

Bocuzzi, Ellen (2012), Bangkok Bound. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Brown, Jeffrey A. and Melissa Loucks (2014), “A Comic of Her Own: Women Writing, Reading and Embodying through Comics”, ImageText, Vol.7, Issue 4: https://imagetextjournal.com/a-comic- of-her-own-women-writing-reading-and-embodying-through-comics/ (Last accessed 15 September 2022).

Chatta, Rasha (2020), “Conflict and Migration in Lebanese Graphic Narratives”, in Kevin Smets et al. (eds), The Sage Handbook of Media and Migration, London: Sage, pp. 597-607.

Chatta, Rasha (2023), “Reclaiming Spaces from the Streets to the Gutter: Sketching Feminisms in Contemporary Arab Graphic Narratives”, in MAI: Feminism and Visual Culture # 10, March 2023. https://maifeminism.com/reclaiming-spaces-from-the-streets-to-the-gutter/ (Last accessed 30 April 2023.)

Chusak Pattarakulvanit (2015), “The Spectre of Modernity and the Modern Spectre”, in South East Asia Research, 23, 4, December, pp. 459-472.

Chute, Hillary (2010), Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. New York: Columbia University Press.

Daou et al. (2021), “Where to, Marie? Stories of Feminisms in Lebanon.” Online: https://tracychehwan.com/2021/03/07/where-to-marie-stories-of-feminisms-in-lebanon/ (Last accessed 30 April 2023.)

Gibson, Mel (2016), “Comics and Gender”, in Frank Bramlett, Roy Cook, Aaron Meskin (eds), The Routledge Companion to Comics, 1st edition, New York: Routledge, pp. 285-295.

Harrison, Rachel (2005), “Amazing Thai film: The rise and rise of contemporary Thai cinema on the international screen”, Asian Affairs, 36:3, 321-338.

____ (2017), “Dystopia as Liberation: Disturbing Femininities in Contemporary Thailand”. Feminist Review, 116, 64-83.

Kepner, Susan (1996), The Lioness in Bloom: Modern Thai Fiction about Women. Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

_____ (2005), Married to the Demon King: Sri Daoruang and her Demon Folk. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Ko Surangkhanang (1995), The Prostitute [tr. David Smyth]. Oxford: Oxford in Asia Paperbacks.

Mills, Mary Beth (1999), Thai Women in the Global Labor Force: Consuming Desires, Contested Selves, New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press.

____ (2014), “Questioning Thailand’s Rural-Urban Divide.” Fieldsights, Cultural Anthropology Online, September 23, 2014.

____ (2012), “Thai Mobilities and Cultural Citizenship”, Critical Asian Studies 44, 1: 85-112.

____ (2008), “Claiming Space: Navigating Landscapes of Power and Citizenship in Thai Labor Activism.” Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 37, 1: 89-128.

____ (2005a), “Engendering Discourses of Displacement: Contesting Mobility and Marginality in Rural Thailand.” Ethnography 6, 3: 385-419.

____ (2005b), “From Nimble Fingers to Raised Fists: Women and Labor Activism in Globalizing Thailand.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 31, 1: 117-144.

____ (2003), “Gender and Inequality in the Global Labor Force”, Annual Review of Anthropology 32: 41-62.

____ (2001a), “Auditioning for the Chorus Line: Gender, Rural Youth, and the Consumption of Modernity in Thailand,” in D. Hodgson (ed.), Gendered Modernities: Ethnographic Perspectives, New York: Palgrave, pp. 27-51.

____ (2001b), “Rural-Urban Obfuscations: Thinking about Urban Anthropology and Labor Migration in Thailand.” City and Society 13, 2: 177-182.

____ (1999b), “Enacting Solidarity: Unions and Migrant Youth in Thailand”, Critique of Anthropology 19, 2: 175-191.

____ (1999c), “Migrant Workers Take a Holiday: Reworking Modernity and Marginalization in Contemporary Thailand.” Critique of Anthropology 19, 1: 31-51.

____ (1998), “Gendered Encounters with Modernity: Labor Migrants and Marriage Choices in Contemporary Thailand.” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 5, 3: 301-334.

____ (1997), “Contesting the Margins of Modernity: Women, Migration, and Consumption in Thailand.” American Ethnologist 24, 1: 37-61.

____ (1995), “Attack of the Widow Ghosts: Gender, Death and Modernity in Northeast Thailand.” In Aihwa Ong and Michael Peletz (eds), Bewitching Women, Pious Men: Gender and Body Politics in Southeast Asia, Berkeley CA, University of California Press, pp. 244-273.

Pasuk Phongpaichit (1982), From Peasant Girls to Bangkok Masseuses. Geneva: ILO.

Seni Saowaphong (1957) [1988], Pisat (12th edition). Bangkok: An thai.

Sidaoru’ang (1994), A Drop of Glass and other stories, tr. Rachel Harrison. Bangkok: Editions Duang Kamol.

Siburapha (2000), Behind the Painting and Other Stories, tr. David Smyth. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Wat Wanlyangkun (1981)[1995], Monrak Transistoe. Bangkok: Phraew.

Filmography

Anna and the King (1999), dir. Andy Tennant

Brokedown Palace (1999), dir. Jonathan Kaplan

Citizen II (1984), dir. Chatrichalerm Yukol

Hangover, Part II (2011), dir. Todd Phillips

Monrak Transistor (2001), dir. Pen-ek Ratanaruang

Ong Bak (2003), dir. Prachya Pinkaew

ixty-Nine (1999), dir. Pen-ek Ratanaruang

The Beach (2000), dir. Danny Boyle

The Impossible (2012), dir. J.A. Bayona